Jerusalem Journal # 172

One step inside the narrow green door tucked obscurely into a massive stone wall was all it took to convince me that the derelict oasis within was like an ancient buried mosaic tile floor, designed to give a message to the world, yet lying unappreciated and in disrepair for years until the timing was right financially, politically, and of even greater importance, providentially.

Ever intrigued by the scores of architectural gems shrouded enigmatically throughout this Land of the Bible, I find an exhilarating rush of curiosity beckoning me to follow all the rabbit trails, exhaust “googled” stories on the subject, and search for ways to weave the past and the present into an uplifting story.

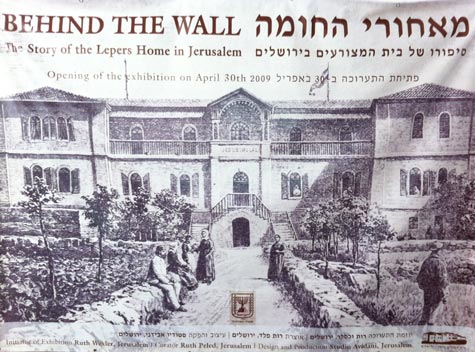

The Jerusalem Lepers’ Hospital is beginning a new chapter

Such is the story of the Jerusalem Lepers’ Hospital whose shroud has recently been lifted and new life is beginning to course through the arching hallways that once echoed with cries of the afflicted. There lepers found acceptance from doctors, nurses, and volunteers whose “raison d’etre” expressed a daily faith in Jesus lived out within embracing courtyards which gave the quarantined a sense of community and spilled out along garden pathways where flora and fauna once promised purpose and nourishment to the outcasts of Jerusalem.

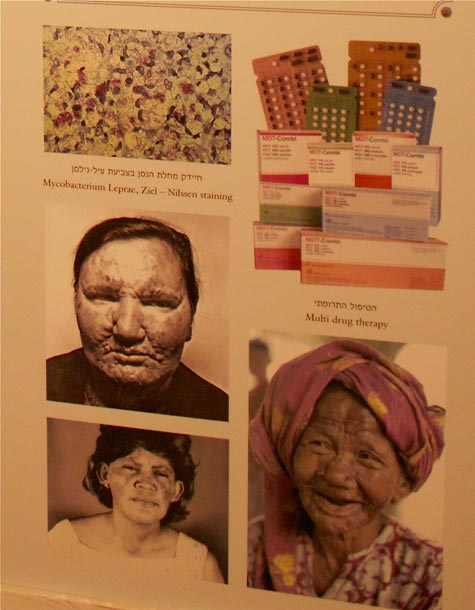

The story of leprosy is an ancient one, clouded by misunderstanding, rife with social stigma. It separated families, caused the leper to be banned from religious practice, and consigned him to life outside the city walls as a beggar. The priest of Biblical times had the sole power to declare a man ritually clean or unclean from the disease. Apart from God’s touch, it was incurable.

The engraved inscription “Jesus Hilfe”(Jesus Helps) reminded hospital leprosy patients of the Jewish rabbi’s power to heal

Leprosy referred to a variety of skin diseases in Biblical times. Hansen’s disease, the modern day “leprosy,” is treatable and is not the feared death sentence of old, so, in 2000 the last patient checked out of Jerusalem Lepers’ Hospital and a long chapter in its fascinating story closed.

Back in 1846, 24-year-old Conrad Schick arrived from Germany to begin a small mission trade school for locals near Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem. His evangelical faith and love of the Bible would leave an indelible imprint on the architectural and archaeological understanding of Jerusalem.

From his discoveries at the Garden Tomb, to building intricate Temple models, to designing grand German-styled edifices throughout the city, this self-taught architect’s desire was that all of the buildings he designed would give glory to God whether by chiseled inscriptions, symbolic motifs, or Biblical pattern. During the course of his lifetime, Schick was commissioned to build three leper asylums in Jerusalem with funds donated by various Christian patrons and organizations.

The first hospital was dedicated in Mamilla (1867), just beyond Jaffa Gate. According to one source, the second, built near the ancient City of David in Silwan (1875), came as a result of a bribe from the Armenian Patriarch who wanted to clear Zion Gate of the leprous beggars beside his church properties. It soon become overpopulated, prompting a third institution (1887) which is Schick’s present-day architectural beauty behind the green door, nestled on a slope in one of Jerusalem’s now affluent and culturally connected neighborhoods west of the Old City.

Historical displays within the hospital give a window into life there

Today, just a stone’s throw away from Zion Gate lies a cemetery tucked in the backyard of my university (Jerusalem University College) where, among the tall pines, Conrad Schick’s gravestone pays tribute to the man who built houses of hope for lepers of Jerusalem during his more than fifty years in the city. He died in 1901 and was mourned by Jews, Muslims, and Christians, attesting to his bridge-building personality and love for all those calling this Holy Land “home.”

On the heels of Schick’s death, German missionary and archaeologist, Gustav Dalman, began creating his vision of a biblical garden on the grounds of the Lepers’ Hospital, hoping that the terraced environment, kept lush by four cisterns on the two-acre property, would be both inspirational and healing to the patients.

It was in this garden, now filled with weeds, crumbling terraces, and stigmatic memories that the seeds of hope are sprouting for Jerusalem’s cultural healing and renaissance at the Jerusalem Lepers’ Hospital. As friend Yoram Honig showed us around the grounds of what will be transformed into the Jerusalem mayor’s vision of a center for film, television, animation, and artistic media, he stopped to point out the words cut in stone over the main entry, “Jesus Hilfe,” encouraging words in the past, and perhaps prophetic words of what is to come.

My experience at the recent Jerusalem Film Festival struck me with the industry’s focus on pain of the past and seemingly little hope for the future. At the Lepers’ Hospital a new season of nurturing stories for the whole family with themes of inspiration and hope is just around the corner—beyond the narrow green door.

Yoram and Gary enjoy a pre-cinema conversation in the garden

Yoram, director of Jerusalem Film and Television Fund, has inaugurated the new center with a series of weekly family films, free to the public, where hundreds come at twilight to kick back on mats and colorful cushions in the cool of the garden. Just weeks ago, families delighted in the message of Rob Reiner’s fanciful tale, The Princess Bride, that true love wins…and it will.

Subscribe to our Jerusalem Journal email here!