Jerusalem Journal # 189

Laundry, strung across countless clotheslines for the world to see, flaps violently in the afternoon wind. Veiled women, cloaked in black, play the clothespins and strings of drying racks like instruments as they adjust their family’s garments to face the shifting sun. Muslim prayer calls, just hours after Friday’s vitriolic sermon at Al Aqsa Mosque, chant from an unknown mosque in the Old City’s Christian Quarter signaling the onset of afternoon prayer cacophonies–– never quite syncing. A silver heart balloon, probably escaping the grip of a young child, sails from Damascus Gate above rooftop laundry as it skirts the monumental minaret anchoring the northwest corner of the ancient Jewish Temple Mount platform known to Islam as Haram Al- Sharif and is whisked eastward to the Mount of Olives.

Westerly winds whip the neighbor’s laundry dry on our terrace above the Via Dolorosa

I move my patio chair from our now-shaded terrace to an adjoining rooftop recently slathered with black waterproofing tar to keep the winter rains from causing the nuns living below to man the drip buckets. With the sun quickly slipping toward the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and western ridge, the black tar offers me some extended warmth as breezes cool. The setting sun appears to be on a teeter totter with a nearly-full moon rising over the Mount of Olives horizon. Muslim holy day is drawing to a close, the Jewish Sabbath is preparing to open, and Christian residents await Sunday church bells. I am living in the rhythm of the sacred.

Sunset casts my shadow on the Sufi Mosque wall as the moon scales al-Fakhriyya Minaret built in 1278

Muslim children chatter and kick soccer balls in the streets below me while a Franciscan monk booms prayers over his portable loudspeaker, leading the faithful along Stations of the Cross on Via Dolorosa as its cobblestoned path turns and winds upward to the Holy Sepulcher. Bells chime from the Latin Patriarchate bell tower for mass. Flocks of white and speckled doves dip and dive gracefully; their aerial laps around domes, minarets, and rooftop terraces cause me to get lost imagining what it is like to see this sacred space from their perspective. It is a typical early spring afternoon in the depths of Jerusalem’s Muslim Quarter.

Regrettably, what has become increasingly typical in my neighborhood has grabbed the international media’s attention and put the spotlight on this age-old crossroads where Jews, Muslims, Christians, and the nations intersect.

After scores of blustery cold and rainy weekends it is finally springtime in Jerusalem. Almond blossoms (the first fruit trees to blossom in Israel) are budding at Damascus Gate, but tragically, the lives of both young Jews and Muslims are being nipped in the bud as a chilling scenario is being repeated where Muslim youths, as young as fourteen, brandish knives to stab Jews. Israeli soldiers and police respond with firepower and the blood of Muslim and Jew now spills and mingles over the ancient stones. It is here that the culture of death intersects the culture of life; the musical rhythm of coexistence is insanely interrupted.

The Hebrew word for almond means “be on the lookout” or “wake up” and this almond tree at Damascus Gate carries a similar message as it stands sentinel at a volatile hotspot.

This morning as Gary and I soaked in the warmth of the sun along with life-giving words from the Bible, the sound of a salvo of gunshots fired from Damascus Gate ricocheted off stone walls to domes to minarets…then chased by a period of silence, before the onslaught of sirens pummeled the Old City walls with a familiar message of “alert.” The rhythm of the sacred was ripped. Again.

The Muslim stabber was shot and killed after attacking two Israeli soldiers. The Old City heaved another sigh of grief, shopkeepers returned to their stone holes-in-the-walls, and business tried to go on as usual. For me, the words of Jeremiah,“The Weeping Prophet,” came to mind as one who mourned. He envisioned the coming destruction and anguish for residents of Jerusalem’s walled city just prior to the 586 B.C. onslaught of Babylonian swords. He, too, saw the nations on an irrevocable course where the sacred was being profaned and only God could intervene.

As residents of the walled city of Jerusalem today, we are witnessing the effects that stabbings and shootings are having on our own lives––extra vigilance as we purchase fruits and vegetables from our street vendor friends or walk to our car through Damascus Gate, occasional re-routing because of blockades, seeing blood washed from cobblestones, police squads garrisoned along our street, and the shroud of grief, like a growing cancer, is stealing away the life of our neighborhood.

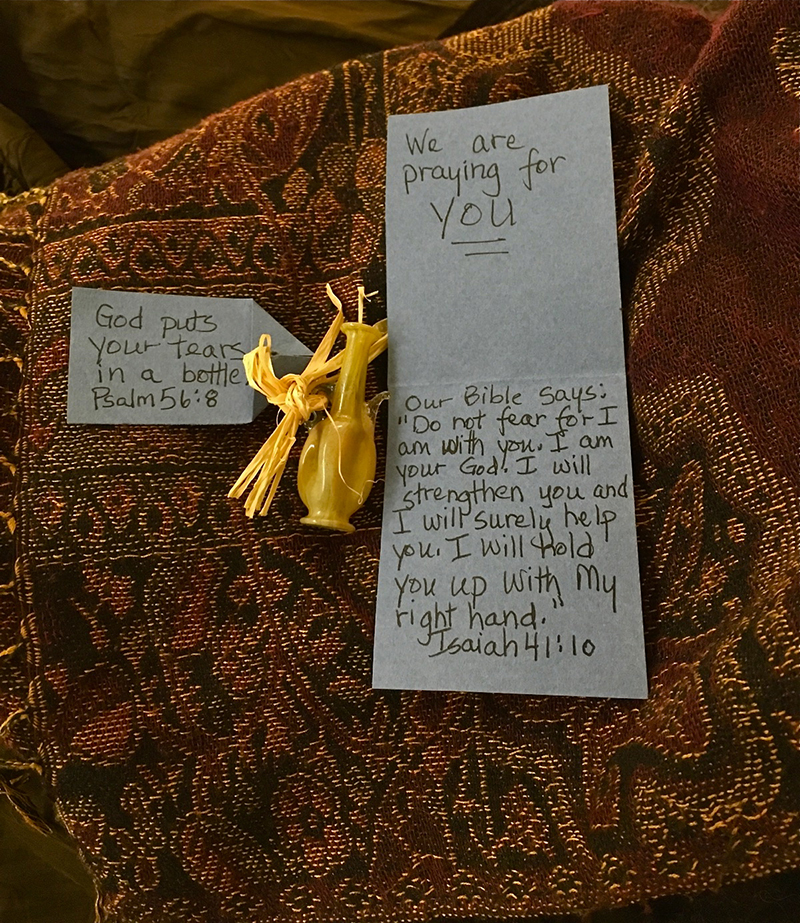

Cancer patient, Hanan, received my gift and words then wept

In the camaraderie of those fighting to live, Hanan became a friend as she and Gary sat in the chemo saloon, while IV cocktails dripped into their veins. My Arabic was far outdistanced by her English. “I cry a lot when I think about what is happening to me,” Hanan said when I asked her how cancer has affected her. “You know, God puts your tears in a bottle,” I said. “Why would He do that?” she queried. “Because He loves you and cares about your pain,” I responded.

This tiny tear bottle carried an invisible healing balm

I wanted Hanan to know those words of hope. I explained how the ancients, even in Roman times here in this land of the Bible, would place the small glass vial under their eyes to catch tears of grief and mourning. The following chemo session I brought Hanan a reproduction of a tear bottle offering a reminder of God’s care for her. In that moment, in that hospital hallway, the rhythm of the sacred eclipsed cancer’s pain, fear of death, and divisions of faith.

Subscribe to our Jerusalem Journal email here!